Indigenous Ancestors & The Insect World

“Indigenous people used insects for a variety of decorative and ceremonial purposes. From cochineal scale was extracted a bright red dye that later was known as Spanish Red. This was used to dye cloth, leather, and to make paint for pottery and cosmetic pastes. Ceremonial capes, masks, and other articles of clothing often incorporated wings of butterflies and moths. Cocoons of certain silk moths were strung together and used as rattle bracelets for ankles and wrists.”—Dr. Tim Drake, Jr.

Upcountry Critters

By Dr. Tim. Drake, Jr.

PENDLETON South Carolina—(The Pendletonian)—The early indigenous inhabitants of North America, most recently known as Native Americans, had daily interactions with a variety of insects. Depending upon the climatic and geographic regions in which they lived, diversity and numbers of insects that affected their daily lives varied significantly. The closer to the equator humans lived, the more insects they encountered on their bodies, in their food, in their dwellings, and destroying their crops.

PENDLETON South Carolina—(The Pendletonian)—The early indigenous inhabitants of North America, most recently known as Native Americans, had daily interactions with a variety of insects. Depending upon the climatic and geographic regions in which they lived, diversity and numbers of insects that affected their daily lives varied significantly. The closer to the equator humans lived, the more insects they encountered on their bodies, in their food, in their dwellings, and destroying their crops.

Nuisance pests were dealt with in a different manner than today because pesticides were unknown to these early cultures. Dried food and seeds were sealed in pottery vessels to keep out insects that might destroy them. Acorns and maize were parched and ground to protect them short-term from destruction by insect larvae. In areas where mosquitoes were a nuisance, fire and smoke were used to exclude them from dwellings. To prevent bites, substances such as mixtures of fat, mud, and wet ashes were rubbed on the skin to discourage biting flies and mosquitoes.

Because of termites in the southern regions of the continent, dwellings and other structures were built of wood that was impervious to termite attack such as bald cypress, locust, pitch-filled pine, and others. Poles set into the ground were charred on the ends that would have contact with the soil, and many structures were elevated on stacked rock piers to keep them above ground. All of these termite prevention measures were later adopted by early European settlers who had no previous experience with these “new world” wood destroying pests.

Insects also served as a vital and dependable food source to many early inhabitants of North America west of the Mississippi River, and they were consumed on a regular basis from the prehistoric period into the historic period, long after contact with Europeans. This was due primarily to the lack of reliable food sources during certain seasons. The natives of the Pacific coast are known to have relied upon insects as a large proportion of their diet. Insects were not utilized as frequently as food by most of the ancient people east of the Mississippi River because of the plentiful wildlife that abounded, seasons that allowed a variety of fruits, acorns, and nuts, and the early advent of diversified agricultural crop production.

The western region of North America was less prone to have large areas of suitable and dependable crop land. Prolonged droughts in the west limited the grazing of large herbivores to areas receiving rainfall and with enough plants to sustain them. This made the consumption of insects for protein necessary in many of these arid areas.

In regions where insects were used as food, various species were used. Grasshoppers, crickets, bot fly larvae (warbles), ants, and various beetle larvae (grubs) were used most frequently. Preparation included drying and grinding into flour, roasting over hot coals, boiling, or just eating insects raw. This source of reliable food prevented starvation in areas where nothing else could survive or be grown.

The use of insects for food has persisted in some Far Eastern, South American, and African cultures to the present time. Insects are among the best low-fat protein sources available for consumption, and it is not unrealistic to consider their expanded use as a primary food source among humans in the future.

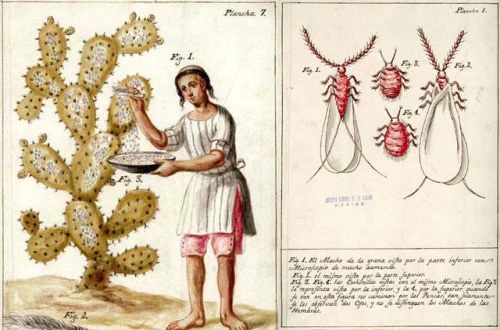

Cochineal is sourced from the female cochineal parasitic insect native to Mexico, Central and South America.

Indigenous people used insects for a variety of decorative and ceremonial purposes. From cochineal scale was extracted a bright red dye that later was known as Spanish Red. This was used to dye cloth, leather, and to make paint for pottery and cosmetic pastes. Ceremonial capes, masks, and other articles of clothing often incorporated wings of butterflies and moths. Cocoons of certain silk moths were strung together and used as rattle bracelets for ankles and wrists.

Certain insects also had medicinal uses. Some insects were dried and ground to powder, the powder then being used in specific medicines and tonics. An example of this is the use of cantharidin found in blister beetles for treating skin conditions and drawing blisters on the skin for various reasons. It is believed that many insect-derived compounds were used, but most of this knowledge has been lost. In some early cultures, there is evidence that large ants were used as sutures to hold together cuts in the skin as they healed, similar to how stitches are used now. The ants were allowed to bite the flesh on both sides of the cut, and then the heads were pinched off allowing the closed mandibles to act as sutures.

Finally, many ancient groups of people used insects in symbolism, and ascribed religious and ceremonial significance to many of them. Images of insects can be found on pottery, sculpted objects, textiles, and other art forms that these cultures left behind. Among ancient indigenous people, the beauty of nature was appreciated and revered. Insects were a part of their environment that could not be ignored and, in many ways, were essential. Now, as then, we find insects to be a vitally important part of our ecosystem and our culture.

![]()