Our New Old Home Place

“There are only two pockets of earth that feel like home to me on all levels: this place between the South Carolina midlands and the great blue wall of the mountains; and Greece. I was a child in the latter; my mother, and many of my grandmothers before her, were children in the former. I idealize neither place but, like Br’er Rabbit in the briar patch, toss me into Attica or Anderson County, and I will go to earth in a flash.”—Elizabeth Boleman-Herring

By Way of Being

By Elizabeth Boleman-Herring

“We need a home in the psychological sense as much as we need one in the physical: to compensate for a vulnerability. We need a refuge to shore up our states of mind, because so much of the world is opposed to our allegiances. We need our rooms to align us to desirable versions of ourselves and to keep alive the important, evanescent sides of us.”―Alain de Boton, The Architecture of Happiness

“It is a great comfort to a rambling people to know that somewhere there is a permanent home―perhaps it is the most final of the comforts they ever really know.”―Ben Robertson, Red Hills and Cotton: An Upcountry Memory

“All great, simple images reveal a psychic state. The house, even more than the landscape, is a ‘psychic state,’ and even when reproduced as it appears from the outside, it bespeaks intimacy. Psychologists generally, and Francoise Minkowska in particular, together with those whom she has succeeded interesting in the subject, have studied the drawing of houses made by children, and even used them for testing. Indeed, the house-test has the advantage of welcoming spontaneity, for many children draw a house spontaneously while dreaming over their paper and pencil. To quote Anne Balif: ‘Asking a child to draw his house is asking him to reveal the deepest dream shelter he has found for his happiness. If he is happy, he will succeed in drawing a snug, protected house which is well built on deeply-rooted foundations.’ It will have the right shape, and nearly always there will be some indication of its inner strength. In certain drawings, quite obviously, to quote Mme. Balif, ‘it is warm indoors, and there is a fire burning, such a big fire, in fact, that it can be seen coming out of the chimney.’ When the house is happy, soft smoke rises in gay rings above the roof.”―Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space

Author’s Note: Since this column was written, in May of 2018, Dean and I have witnessed a world of change in our own lives, and the lives of all in our town, weathered a pandemic and a terrifying hurricane, added on a cathedral-like addition to the house at the corner of Duke and Micasa, and lost beloved neighbors while welcoming new ones. We even now have a dog! As my maternal grandfather, Lon Schenault Boleman, of Townville, would say, the Lord willing, the creek don’t rise, and the republic prevail, we will remain here for the duration.

PENDLETON South Carolina—(The Pendletonian)—December 2024—Prepare yourselves: if ever there is a lede in one of my essays, it shall be buried. It seems I prefer to meander towards meaning; always approaching; rarely arriving. Either that or, by writing, and at length, I sometimes happen upon small-t truth. By writing, in writing, I figure out what it is I’m trying to say; what it is I know. In writing, I draw the thing itself by means of blowing smoke rings: I look up (and perhaps you do, too, for a moment), and see something almost corporeal . . . before it vanishes into thin air.

PENDLETON South Carolina—(The Pendletonian)—December 2024—Prepare yourselves: if ever there is a lede in one of my essays, it shall be buried. It seems I prefer to meander towards meaning; always approaching; rarely arriving. Either that or, by writing, and at length, I sometimes happen upon small-t truth. By writing, in writing, I figure out what it is I’m trying to say; what it is I know. In writing, I draw the thing itself by means of blowing smoke rings: I look up (and perhaps you do, too, for a moment), and see something almost corporeal . . . before it vanishes into thin air.

All this past year—no, I lie—for the past three years of Our Floridian Banishment, I have dreamed elaborate architectural dreams. In my sleep, I have wandered through cities only just somehow created in my sleeping mind’s eye. With intimate, lost others, who no longer walk the planet with us, I have packed and unpacked virtual suitcases in virtual rooms; mounted ethereal stairs; conducted ghostly business; gardened in midnight gardens.

The night city, and its structures, were, to this dreamer, Athens, Greece, but an Athens that has never been: out of time, lightless, if, while I slept, absolutely real to me.

Perhaps my sleeping brain is simply starved for oxygen, or perhaps, in Florida, I had no scope for creativity, and was compelled to erect castles in the air. But for some time after waking, it was impossible to convince myself that the Plaka through which I had just been walking was imagined, and not real. The doors made a sound upon closing; the wind in the ruined gardens felt cold upon my cheek—for this was an Athenian moonscape. Perhaps the city I envision in spirit is Athens after its early-2000s economic ruin: dark, under psychic siege, but still beloved.

On the first of January, though, these dreams abruptly ceased after Dean and I drove north, out of Florida, through Georgia, and on up into the Piedmont of South Carolina. Drove home, in fact, though I was born elsewhere, and have lived only nine of my 66 years in the birthplace of my mother and grandmother. Home, though Dean has never lived here and never, before two years ago, desired to do so. By all rights, Upstate South Carolina should feel as alien to me, to us, as any other deep-red state, but who knows what is bred in the bone?

There are only two pockets of earth that feel like home to me on all levels: this place between the South Carolina midlands and the great blue wall of the mountains; and Greece. I was a child in the latter; my mother, and many of my grandmothers before her, were children in the former. I idealize neither place but, like Br’er Rabbit in the briar patch, toss me into Attica or Anderson County, and I will go to earth in a flash.

So. In Florida, dreaming of Greece, I began sketching, in my mind, a plan for a house in South Carolina: ah me, the logic of the heart, which wants what it wants.

One must live in an exquisite state of denial to begin building a new home in one’s middle 60s, but Dean and I decided that, while it may be late, it might not be too late.

In memory, I could see my maternal grandparents’ Classical Revival farmhouse, still standing, still accessible to analog visitors, in Townville, South Carolina; and Dean and I were soon to walk through the structure in real time.

At the Anderson County Court House, a clerk retrieved for me the Smith and Boleman families’ original deeds and plat for the property. Built at the end of the 19th century, the old home place had been standing some 20 years when my mother, the last of the Boleman children, was born. I would visit, as the last of the Boleman-diaspora grandchildren, in the early 1950s, flying into Atlanta from Los Angeles, and driving east with my mother’s sisters and their husbands.

That white frame house, for some unknown reason, was—is—a touchstone for me. Though I grew up in Pasadena, Athens, Greece, and Chicago, and visited my grandparents for only a week here and there through my first decade of life, the Townville house satisfies some deep atavistic (from Latin atavus, “ancestor”; from at + avus, or “grandfather”) pattern that is deeply satisfying.

Built by some simple local carpenter, and similar but not identical to other large farm houses in Townville, the house made deep psychological sense. There was an allée of pecan trees that stretched a quarter of a mile from street to front door, and then, there was the virtual moat of the wraparound porch.

The front rooms, off a wide middle hall, were for the public: twin parlors, only one of which later became the room where a desperately ill child might be quarantined—my mother, for example, with diphtheria.

Behind those parlors, and only accessible from the hall, were the bedrooms, to the left, and the dining room and kitchen, to the right. The privy, originally in the back yard, eventually morphed into a proper bathroom, in my time. The chicken coop and barn were situated behind the house. I was sent out for eggs, when I was tiny, and had to brave fierce geese on my way to the chickens.

This household “logic,” of public and private space, for master, mistress, offspring, and kind, is as old as Homo sapiens. Older.

In At Home: A Short History of Private Life, Bill Bryson writes of Skara Brae, the c.3100-2500 BCE settlement in Orkney, Scotland:

“What never fails to astonish . . . is the sophistication. These were the dwellings of Neolithic people, but the houses had locking doors, a system of drainage and even, it seems, elemental plumbing with slots in the walls to sluice away wastes. The interiors were capacious. The walls, still standing, were up to ten feet high, so they afforded plenty of headroom, and the floors were paved. Each house has built-in stone dressers, storage alcoves, boxed enclosures presumed to be beds, water tanks, and damp courses that would have kept the interiors snug and dry. The houses are all of one size and built to the same plan, suggesting a kind of genial commune rather than a conventional tribal hierarchy. Covered passageways ran between the houses and led to a paved open area—dubbed ‘the marketplace’ by early archaeologists—where tasks could be done in a social setting.”

I suspect the daughters of Orkney, upon first seeing Skara Brae after an 1850 storm revealed the settlement, experienced a flash of fellow feeling for the Grooved Ware People who had once lived here:

“Seven of the houses have similar furniture, with the beds and dresser in the same places in each house. The dresser stands against the wall opposite the door, and was the first thing seen by anyone entering the dwelling. Each of these houses had the larger bed on the right side of the doorway and the smaller on the left. Lloyd Laing noted that this pattern accorded with Hebridean custom up to the early 20th century suggesting that the husband’s bed was the larger and the wife’s was the smaller. The discovery of beads and paint-pots in some of the smaller beds may support this interpretation. Additional support may come from the recognition that stone boxes lie to the left of most doorways, forcing the person entering the house to turn to the right-hand, ‘male,’ side of the dwelling. At the front of each bed lie the stumps of stone pillars that may have supported a canopy of fur; another link with recent Hebridean style.”

For me, the floor plan, dimensions, and Victorian details of Lon and Abalena Boleman’s house, where my mother and her four siblings were born and reared, stands in (in memory) for me, as “home,” though I never lived in the house, nor spent even one night there. My mother, who fled South Carolina at 19 as one would The Plague, rarely spoke of her Depression-era childhood in Townville, nor of the house which, for her, represented only suffocation and stasis.

Beth Boleman Herring, a jazz singer and thespian, had been “made” for Broadway. Her daughter, on the other hand, is content to return to Mayberry. My mother, who had a home, was happy to leave it; I, who’ve never had one “of my own making,” am happiest to replicate that Townville farmhouse . . . in Pendleton, South Carolina.

Perhaps, by early this summer, the word will finally become flesh.

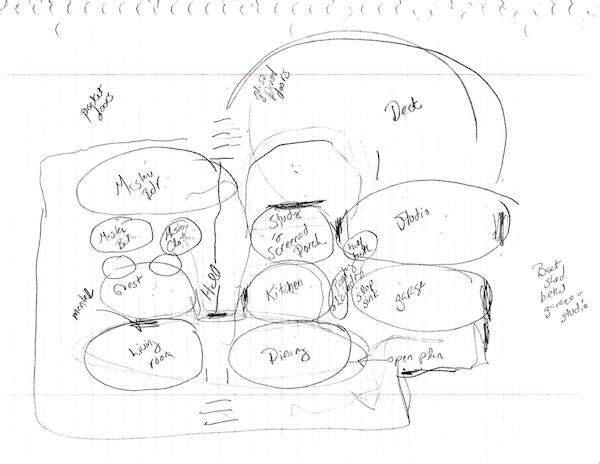

I drew up our plan on a sheet of lined notebook paper, remembering the wide central hallway in Townville, the wraparound porch, with its bent willow porch swings, and the tin roof.

The rooms, as pictured in my first primitive sketch, are drawn as ellipses, so the house piles up, extended circle upon extended circle. One approaches from the street, climbs the stairs to quite some height, crosses the wide porch, and then enters the public rooms of the hypothetical dwelling . . . and encounters a wall and one door, behind which the private rooms and the hall, the spine and heart of the house, are hidden. Our builder, the son of friends, fed all my nonsense into his computer and, eventually, came up with a beautiful, detailed blueprint from which he has worked, in situ, since the winter.

You may ask, at this juncture, but are not two people to live In this no-longer-hypothetical structure? And is not the second person, the one who, in Skara Brae, would make his bed to the right side of the door, a native of New York? What does he think of moving to South Carolina, and of living among Southern Baptists, rice-eaters, and Republicans?

Well, it was Dean who made the decision to move here; and Dean who convinced me.

Two years ago, we made our annual visit to South Carolina for Pendleton’s April Spring Jubilee, when tens of thousands of visitors converge on the tiny town for an arts, crafts, and music fair. We were in search of a new life in a new home, and made the rounds of houses for sale in Anderson County but saw nothing to our liking. In our hearts, we wanted one of the historic homes in Pendleton, but none was for sale.

Then Dean—he who has never built a house—got it into his head that we could just build a home in Pendleton. Problem was, and is, there is no land left for sale in the town, and a building boom has ensured there’s no land left even around Pendleton.

About a block off the town square, though, we encountered an old friend, artist John Acorn, and Dean, that son of Rochester, New York, asked him if he knew of anyone local with an acre to sell.

John stunned us both when he said, “I do,” and proceeded to walk us a block further where, indeed, the only plot of land left in the tiny town, two blocks off the square and a block from the Pendleton Little Theater stood, wooded in magnolia and chestnut.

“Peggy and I had planned to build a smaller house here,” said John. But it was not to be and, yet, something compelled him to hold on to the property.

Dean said then, stunning his wife into silence, “Would you sell it to me?”

“I would!” replied John, and a handshake sealed the deal . . . for two long years, as we set about selling our house in Florida, putting all we owned into storage there, and renting a house in Summerfield, near our storage units, till our builder was ready and able to break ground.

Since January, Dean and I have hovered in place, living in “student housing” in Clemson, on the same hallway as Clemson University’s basketball team, and driving over daily from Clemson to nearby Pendleton, to our building site, where heavy spring rains have delayed and delayed the process of bringing our house into being.

At 66 and 68, respectively, we live in hope of having our own roof over our own heads before the corn ripens.

For half a century, I lived a wanderer’s life—and Dean, as well—before we met, and lived, in a house others had built, on the outskirts of New York City.

Now, in our lives’ fourth act, we have made the leap of mad faith it takes to throw up a new house in these uncertain and challenging times, for individuals and for our species. We hope to grow old, truly old, together, in our new home place, and then leave it to others for whom its lineaments will hold meaning and make sense.

But, finally, the conception of the house, of any house, is the thing: the conception, and the building. As South Carolina’s great prose-bard, Ben Robertson sums it up, in Red Hills and Cotton: “It was not the goal that really concerned us, the journey was the thing. Who ever reaches any goal? From what journey can we return? We know of the poverty about us, of the work and worry, but we know of a degree of freedom, of a stunted beauty. We have warm open days and sunshine in Carolina. Much is denied us. But what we have, we have. And an attitude is more powerful than any circumstance.”

![]()

Note Regarding the Second Image Above: “The Freeman-Felker House is a historic house located at 318 West Elm Street in Rogers, Arkansas. It is a large two-story wood frame structure designed by local architect A. O. Clark and built in 1903 for a banker. The house has a pyramidal roof and a wraparound porch with Classical Revival detailing. A large gable projects slightly on the main facade, with a Palladian window at its center. The house includes a sun-room, added in the 1930s by its second owner, J. E. Felker, and also designed by Clark.”

Further Reading: For those interested in a long, representative excerpt from that classic portrait of Upstate South Carolina, I submit, from Red Hills and Cotton: An Upcountry Memory, by Ben Robertson (1941), Chapter I, Page 9:

“I and my kinfolks are Southerners of the inland and upland South. We and the ten million like us call ourselves the backbone of the Southern regions, the hickory-nut homespun Southerners, who while doing a lot of talking have also done a world of work. We are of Scotch-Irish stock, improved Scots of Ulster extraction, and it has never been said of any of us that we have held back from sounding our horn. We are forthright and outspoken. We are plain people and our houses are plain―you will not find on our front piazzas tall white columns holding up the roof. We are Southern Stoics. We believe in self-reliance, in self-improvement, in progress as the theory of history, in loyalty, in total abstinence, in total immersion, in faithfulness, righteousness, justice, in honoring our parents, in living without disgrace. We have chosen asceticism because all of our lives we have had to fight an inclination to license―we know how narrow and shallow is the gulf between asceticism and complete indulgence; we have always known much concerning the far outer realms, the extremes. We have tried throughout our lives to keep the Commandments, we have set for ourselves one of the strictest, sternest codes in existence, but our country is Southern and we are Southern, and frequently we fail. In the end we stake our immortal souls on the ultimate deathbed repentance. We put our faith in the promise of Paul the Apostle that in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, we shall be changed.

“We believe in hard day labor, and in spite of all our cooks and bottle-washers we hold that every farmer should take his turn in the field―he should plow and pick cotton and thin corn. All that eat should sweat. Some of us, of course, have never sweated, but always we have thought we ought to. We are formal―we address God in prayer as “Thou” and “Thee.” We are intimate―we like to call old married ladies by their lost maiden names, “Miss May Belle,” “Miss Minnie Green.” We flatter―we call men “Colonel” and “Judge” and “Major.” Of all the colonels among my kinfolks, only one ever really held that rank. My Great-Uncle Bob was a real colonel. Once he had commanded a regiment of infantry in the army of General Jackson. The rest of our colonels were like my cousin Colonel Tom, of whom my father said: “He is just a Southern colonel.” He looked like a colonel, so we called him one. We honored the distinction of his stately appearance. Many of my kinfolks have charm―if I do say it myself. Like almost all Southerners, white and black, we were born with manners―with the genuine grace that floods outward from the heart. I must add also that many of us, far from home, have learned that we can trade on our Southern manners. We do not hesitate to do so, either ―we flatter and charm when we can without a flicker of regret.

“As Southerners, it is essential to my kinfolks that they live by an ethical code, that they live their lives with dignity to themselves, that they live them with honor. A Southerner who loses his honor loses all, and he had rather die than live in disgrace. Honor is at the base of our personal attitude toward life. It is not defeat that we fear, it is the loss of our intimate honor. We do not only disgrace ourselves, we disgrace all the others, and we cover our heads, for each of us was born in the image and glory of God.”

![]()

To order Elizabeth Boleman-Herring’s memoir and/or her erotic novel, click on the book covers below:

3 Comments

Will Balk

This IS an exciting new venture, dear Elizabeth! It’s a fine inaugural issue. I can’t wait for what comes next. Big congratulations.

Caroline Kirkley Taylor

Wonderful!!! I read every single article with great interest and increasing joy as I loved the topics and depth of information!!

I want to in particular say that your Article Elizabeth- 1. Where you explain how and why you write- explains a lot about what i have loved getting to know about you- and the way your mind works- and 2. I love love love Ben Robertson’s book- so much- I have 2 copies – and often recommend it as such a great history lesson of the Upstate of SC in that era … and small world- my dad’s mom- Mrs Nancy Kirkley- married for a 2nd time to a dear family Friend- Billy Bowen- fellow retired Ag Ed professor from Clemson and colleague of my grandfather FE Kirkley, SR- and he, “Granddaddy Billy” is the one who told me of Red Hills of Cotton- Ben was his cousin!

Keep up the great work! I look forward to future issues! Not just for Pendleton residents- so I will share as well!

With admiration –

Your friend,

Caroline

Eguru B-H

Dearest Caroline,

We think of you daily, here on Duke Street, and your words above echo and reinforce your mother’s constant, loving support of me, and my various ventures. How I miss her, and how grateful I am to have you!

Do drop The Post & Courier editors a note. Originally, they were going to produce, quarterly, an analog version of The Pendletonian. I still believe it would do them, and us, a heap of good!

Do NOT be a stranger!!

Love to you and yours these holidays….

e